All Art Is a Tragicomic Holding Action Against Entropy

one. Introduction

In social-ecological systems (SES), such as urban h2o service supply and consumption systems, institutional alter does not but come across social complexity, but it is besides embedded into wider and complex ecological systems. Nosotros define such a [1] SES as an "ecological organisation intricately linked with and affected past i or more than social systems" [2], cf. [3,iv]. In SES, institutions "regulate relationships among individuals and between the social and ecological systems (…and therefore) link social and ecological systems" [5]. Large parts of the system into which institutions are embedded are, therefore, beyond the researchers' or the policy-makers' control. Furthermore, as nosotros volition debate, in gild to change the way institutions regulate relationships between social and ecological systems, what we describe as multifaceted institutional change needs to unfold. This combines several notions of institutions and their interrelated modify. Thus, we reconceptualize our understanding of urban water management and its governance inside this framework, in which we refer to the processes whereby elements in municipal gild wield power, authority and influence and enact policies and decisions apropos public life, environmental, economic, social and cultural development within the wider ecological system.

Confronting this groundwork, the authors evaluate Action Enquiry (AR) within processes of intended institutional modify, which has widely been termed institutional design [6]. Bobrow and Dryzek [seven] argue: "design is the creation of an actionable form to promote valued outcomes in a particular context". We reason that AR is particularly useful, considering it functions as a conduit for carrying change. This argument is supported by the evaluation of the empirical groundwork we encountered in Volos Metropolitan Area, Hellenic republic, where the implementation of the European Water Framework Directive (WFD) required meaning changes in water management practices.

In what follows, we discuss the potential of action research to meet the described challenges entailed in intended institutional change for social-ecological organization direction, focusing specifically on urban water management. Our aim is to nowadays the key features of AR and discuss its value for initiating, accompanying and agreement intended, (multifaceted) institutional change in complex SES, such every bit urban water systems.

The paper first describes the need for multifaceted institutional alter that emerges from the legal and procedural requirements of the WFD. And then, it describes our conception of multifaceted institutional change, relying on a "multi-layered" understanding of institutions and the mechanisms that drive their change and connects the implications of the WFD to this agreement. Further, the newspaper introduces AR and describes its potential within processes of intended institutional modify, and finally, it illustrates its employ in the case of changing urban water management in Volos, Greece. Through this instance, we address the question of how science can engage with the problem of producing valid knowledge and legitimizing its findings and policy recommendations in complex SES in a manner that fruitfully informs multifaceted processes of intended institutional change.

2. The Water Framework Directive and the Instance of Multifaceted Institutional Change

The European H2o Framework Directive (WFD) 2000/60/CE [8] requires significant changes in the procedures and performance of water management all over Europe. It replaced older pieces of European h2o legislation, such as the Directives 76/160/EEC [nine] (quality of bathing water), 76/464/EEC [ten] (water pollution by discharges of certain dangerous substances), lxxx/68/EEC [11] (groundwater protection against unsafe substances), 91/676/EEC [12] (nitrates directive) and 91/271/EEC [13] (urban waste water treatment). At the time, it reflected the changing socio-political and economic context of the 1990s: (1) the increasing internationalization and complexity of water resource management; (ii) the rising number of actors and institutions involved; (3) the newly vested economic interests in h2o supply; and (4) the growing concern and sensitivity towards ecology protection [14]. The Directive promotes an integrated and holistic water management approach, targeting all water bodies and pursuing a sustainable use of h2o resources, both from a quantitative and a qualitative perspective. Economic, environmental and ethical bug are incorporated in the overall aim of achieving good h2o condition by 2015 [15,16].

The Directive's objective of "good ecological and chemical status of all European waters" introduces an indirect incentive for member states to address functional, temporal and spatial interrelations betwixt multiple water uses, various water systems and the institutions to mediate their interdependencies. Petersen et al. [17], therefore, contend that a key shift in the public mandate to regulate water use has occurred. The WFD has significantly enlarged the telescopic of responsibilities of the state in water management by enervating provision of expert environmental status, a task, which the authors acquaintance with greater state interference.

Specifically, the WFD introduces a series of key innovations, including the organization of h2o management around river basins and the widening of participation in water policymaking [18]. For river basin overviews of fundamental characteristics, a prediction of the impact of human activity on the quality and quantity of the basin's waters and a programme of measures for the achievement of good ecological and chemical status accept to be devised. The corresponding processes oft require significant changes in national water management and planning practices (cf. [1]).

The elaboration of such plans is informed past the operationalization of the directive in so-chosen pilot river basins. Measures to meliorate waters are to be founded on in-depth information gathering exercises. The WFD contains further institutional prescriptions concerning water management, such every bit "increasing public participation and balancing interest of various groups", too as ensuring that the "price charged to water users integrates the true costs" [19]. Wide integration with other policies and coordinated procedures for information gathering throughout stock-taking exercises are besides prescribed. The procedure past which the WFD was elaborated, its transposition through the so-called Common Implementation Process in which loftier-level water managers participated, has to be seen equally a tiptop-down process, which obtained local, bottom-up input and legitimization only in a very abstract fashion [8]. Only afterward, participation and consultation exercises throughout the elaboration of River Bowl Plans potentially allowed for more than lesser-upwards involvement, necessitating a case-past-case analysis of the construction of legitimacy. Several authors take concluded that participation exercises have varied greatly [20]. Below, we nowadays activeness research and examine its value concerning processes of gathering data about h2o management issues, bringing actors together in order to develop and legitimize measures and potentially changing water use and management culture and, at the aforementioned fourth dimension, researching such processes of transformation. The processes of implementing these various aspects of the Directive, meanwhile, became a veritable field of social scientific discipline studies. Early assessments highlighted the need for collaboration beyond sectors and levels and set out agendas for enquiry to support the implementation of the WFD [21,22,23,24], cf. [25]. Some other set of studies highlighted the potential role of social learning every bit a necessary ingredient to meet the integrative direction challenges and the uncertainties involved in achieving the objectives of the WFD (cf. [26,27,28]). As nosotros will argue in Affiliate 4, activity research addresses many of these challenges in designing processes that contribute to achieving the integrative aims of the WFD.

The WFD has noun, performance-related and procedural aims with regards to water management. In all European member states, changes are required in water management practices, and therefore, all-encompassing institutional alter, formal and informal, is unsaid. As such, the WFD constitutes a typical height-downward policy, aiming at changing water institutions. For doing so, information technology relies on a diversity of mechanisms existence aware of the need for interrelated, multifaceted institutional change. For example, prescriptions apropos the organization of water planning and direction in river basin districts aim at the alter of institutions external to people's practices. They require water managers and users to adapt in the face up of possible European sanctions in instance of non-compliance. Similarly, prescriptions concerning the achievement of good ecological and chemical status and the introduction of water pricing policies presume changes of rational actors' practices, as a consequence of changes in formal requirements. In contrast, reliance of the WFD on extensive data and cognition gathering as an input for water planning can exist considered a prerequisite for endogenous mechanisms triggering institutional alter through learning virtually challenges for h2o management. They are necessary to accommodate to the substantive aims of the WFD and adaptation of practices in order to achieve these aims. Similarly, the Common Implementation Strategy (CIS) of the WFD aims at institutional change by bringing European loftier-level water managers into a collective learning process. Furthermore, the WFD's prescriptions on participation and consultation oft require changes in formal institutions in order to avoid EU sanctioning. They finally aim at unleashing data exchange and learning processes among local water users and managers in guild to depict upwards cohesive and legitimate measures for attaining the substantive objectives of the WFD. Thus, in the context of the WFD, intended institutional change relies on an understanding of institutional change as beingness multifaceted. In what follows, we volition conceptualize institutional change to permit us a better agreement of European water governance inside which our example volition exist examined.

3. Conceptualizing Institutional Modify

In what follows, we characterize different conceptualizations of institutional change, so as to unfold our understanding of intended institutional change equally "intended multifaceted institutional change", every bit implied in the WFD. This argument prepares the basis for our evaluation of action enquiry in regard to its ability to facilitate such multifaceted institutional modify.

Institutions regularize human being, behavioral interdependencies by structuring humans' interaction [29,30]. They provide information and distribute costs and benefits from actions and, in that way, cater for an immaterial structure that informs courses of action [31]. Institutions are embedded into a complex ready of interrelations with other actions and institutions. In contexts where interdependence between actors is mediated by complex, non-linear, biophysical systems, such as not-man nature, we assume that many of the institutional and biophysical interrelations at pale are meaning, but insufficiently understood [32]. In this paper, we specifically look at intended institutional change, implying deliberate replacement of existing, formal (backed past a tertiary political party power and valid for entire collectives, often codified) or informal institutions (idiosyncratic, often specified to situations and contexts and not codified) or the creation of new institutions with the aim of irresolute de facto institutions regularizing actors' interactions.

A variety of theories of institutional change accept been proposed [33]. Authors distinguish between an endogenous or an exogenous role for institutions in the way they shape people'due south behavior, and they distinguish betwixt lesser-up, induced, decentral institutional modify and top-down, imposed institutional modify. [34,35]. Schmid [29] proposes a classification highlighting functional, power and learning evolutionary theories of institutional change.

Rational choice based theories of institutional change view institutions as exogenous to actors. In such theories, actors concur stable preferences and behave instrumentally in maximizing attainment of these preferences. They act strategically and summate their deportment in regard to the outcomes of the different options they have [36]. After the introduction of "new" institutions, actors will determine for the option with the everyman ratio of costs and benefits/or perceived utility gains and losses. Therefore, given knowledge most their institutional selection and how they evaluate them, choices about institutions go predictable. Theesfeld [37] captures the essence of distributional theories of institutional alter when she describes the process of institutional change as negotiation between differentially resourceful actors (cf. [38]). The economic theory of institutional alter, on the other hand, holds that institutions that effect from actors' choices will be Pareto-efficient nether consideration of the costs of coordinating actors and organizing transactions (i.e., transaction costs). Thus, it predicts that actors will choose the institution that is most benign in terms of transaction costs. However, competition between institutions is assumed to result in socially optimal institutions [38]. We would equate this with a functional theory of institutional change [35]. In contrast, in what we termed the distributional theory of institutional alter, institutions reflect the bargaining positions of private actors and their incentives derived from the distributional outcome associated with different institutions. In either theory, institutional change as a result of changes in actors' behavior, because of changes in external incentives implicated in rules, can exist considered equally predictable. This is considering actors either follow self-seeking preferences or a social optimum. Thus, changing institutions and behavior in an intended way seems possible.

March and Olsen'southward logic of appropriateness offers an alternative theory, focusing on legitimate rules virtually informing part-specific activeness in well- or less well-specified situations. According to March and Olsen ([39], p. 4): "Actors appoint into a process of matching of identities, situations and behavioral rules, which is based on experience, expert knowledge or intuition". Role expectations or advisable behaviors make up one's mind more than or less precisely what appropriate activity is. In this formulation, institutional change tin emerge as an outcome of changes of perceptions almost roles, identities, normative values, cognitive frames and rules. Still, the outcomes of intended institutional change are essentially unpredictable in this context, but depend on the specificities of the problem situation and the way in which experience, proficient cognition or intuition are applied.

In the theories of institutional alter described above, institutions are viewed every bit predominantly external to actors. In other theories, though, at least their source is viewed as endogenous to actors, implying that also their change requires endogenous, cognitive alter [40]. For example, Hodgson'south idea of habituation distinguishes habits every bit the key element linking institutions to individuals. Habits change as a issue of "reconstitutive downward causation" ([41], p.108). Thus, social structures act to some caste upon individual habits of thought and activeness [41]. This kind of conception of institutional change tin be considered an evolutionary, open-ended view ([42], p. 186).

Some authors relate the latter perspective, engendering endogenous cognitive modify to different types of learning. Stagl, for instance, details learning as an interdependent, intermingled processes of social organizational and individual-based learning [43]. While usually associated with the economic theory of institutional alter, even Northward captures the multiple mechanisms through which institutions change: "information technology is unremarkably some mixture of external modify and internal learning that triggers the choices that lead to institutional change" [44]. He farther argues that responsible factors are changes in relative prices and learning, leading to new mental models [45]. Due north derives that individuals compare gains from an existing institutional framework to gains from devoting resources to altering that framework and that "Bargaining strength and the incidence of transaction costs" are fundamental [45]. We follow this understanding and meet institutional modify every bit a phenomenon interrelating determinants of the regularization of practices that are exogenous and endogenous to actors. Thus, changes in exogenous institutions, at some signal, may touch on internalized habits of actors, likewise as changes in habits may "upwards-scale" to changes in exogenous or even formal institutions, whose change is subject to rational evaluation, contest or bargaining, depending on the specific context of institutional choice.

The perspectives presented can be related to different understandings about the possibility to change institutions and the underlying methodologies practical for this purpose. Alexander [46] usefully distinguishes objective and subjective institutional pattern. In objective institutional design we presume that we take theories that tell us how to bear on intentional institutional change and deliberately create and change institutions, with the aim of affecting practices. Still, outcomes are presumed to be anticipated. We associate this with an understanding of institutional change as propagated past rational choice orientations. In contrast, in subjective-dialogic institutional design, we do not have conclusive understanding nearly how institutional change unfolds and need to understand the transformation that is unleashed by intended institutional change; we require descriptive-explanatory noesis based on reflexive experience, empirical ascertainment and assay in order to come to adequate proposals that guide development of institutions into the intended management [46]. Outcomes are presumed to exist unintended and unpredictable, to a large extent. This agreement would be associated with theories that emphasize the endogenous, cerebral dimension of institutions, equally in learning and development-oriented theories of institutional change. In the latter category, we would include the agreement that institutions mediate relational dynamics between a social and a biophysical organisation [27].

As nosotros described and so far, the WFD is a typical endeavour, common in many European directives, of a tiptop-downwardly attempt to alter water institutions. However, it integrates many innovative aspects. The different conceptualizations of institutional change discussed here are viewed as "intended multifaceted institutional change", equally implied in the European WFD. In what follows, we will illustrate the potential of Action Research to facilitate the process of multifaceted institutional change.

four. The Methodological Value of Activity Enquiry

The basic principles of action research tin can exist traced dorsum to the original work of Kurt Lewin [47] and John Collier [48] and to Chris Argyris'southward notion of activeness science [49]. Many of the epistemological foundations of action inquiry, such as being context bound, focusing on practical problem-solving, seeking for diverseness in approaches, having strong democratic aspirations, embedding the notion of interdisciplinarity, highlighting the importance of community participation [50], have a lot in mutual with various disciplines and their methodological toolbox (with ecological economics, for instance); however, it was not until the key piece of work of Reason and Bradbury [51] that the quality of this methodology was reinstated as a concern and the term "activity inquiry" was established as the umbrella term for participatory and activeness-oriented approaches.

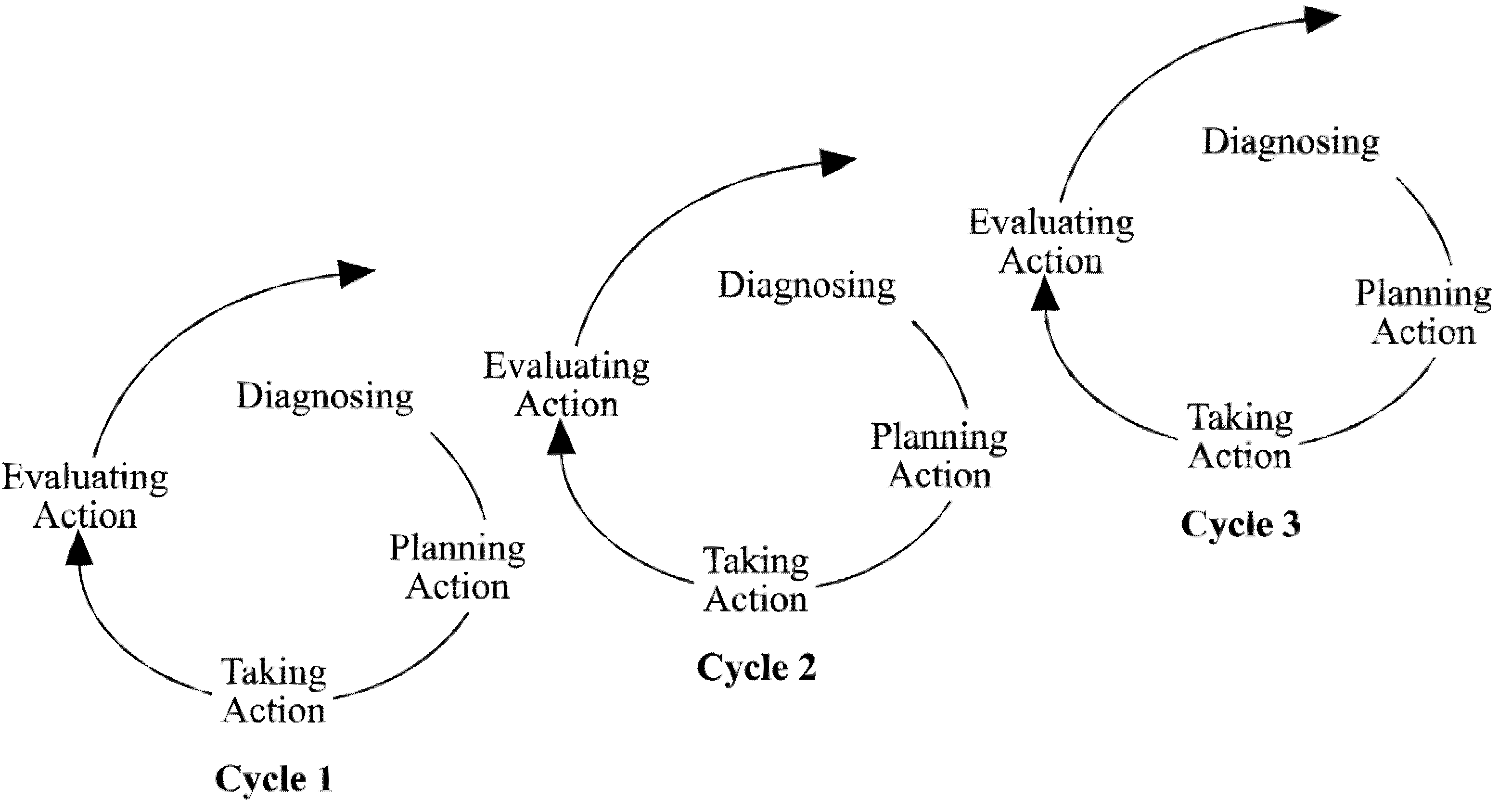

Action research is a reflective research methodology that crosses and bridges various disciplines and tin exist understood as a special way of thinking about scientific inquiry, as well as an attitude towards the office of science inside society [50]. It moves beyond unmarried-dimensional knowledge created by outside experts sampling variables to an interactive research process, where knowledge is generated through a reflective cyclical process of continues improvement (Figure i), where researchers actively participate in the research procedure past becoming the object, as well every bit the subject field, of assay [52].

Figure 1. The continuous cycles of Action Research (source: [53]).

Figure 1. The continuous cycles of Activeness Research (source: [53]).

Co-ordinate to Reason and Bradbury [51], such a process balances problem-solving actions implemented in a collaborative context with data-driven analysis, in gild to understand underlying causes and enable futurity predictions nigh change. Past exposing himself to a certain situation under study, the researcher understands an institutional modify process in order to transform the social environment through the disquisitional inquiry. From this perspective, the analytic task is to study action-related constructs, by "unpacking taken for granted views and detecting invisible only oppressive structures" ([54], p. 9).

Later on the long process of AR's development, Reason and Bradbury [55] offer an inclusive definition of activeness research:

"a participatory procedure concerned with developing applied knowing in the pursuit of worthwhile human purposes... It seeks to bring together activity and reflection, theory and practice.".

([55], p. four)

Generally, a researcher uses certain scientific procedures and conventions to make it at proposals for institutions that are to shape individual behavior. In doing so, we argue that scientists explicitly or implicitly always rely on a theory that informs institutional design.

Traditionally, action researchers, notwithstanding, reject theories associated with positivist research methodologies [56]. Instead, they are fundamentally interested in the interpretation of a procedure and of the resulting change and, thus, run across positivist theorizing as antagonistic to these aims [56]. Broadly speaking, these characteristic of AR suggest that theory needs to be both sensitive to the meanings participants give to their situation (and equally such, cannot be decided earlier the involvement of the researcher), even so get across these to explore unseen causal dimensions of actors' behavior and the environment and the interactions betwixt the social and ecological system.

Buchy and Ahmed [57] name the example of the collaboration betwixt NGOs and academics to highlight this distinctive characteristic of AR. This collaboration, Buchy and Ahmed argue, offers great potential for improving practical intervention, also as testing theories and challenging theoretical assumptions. However, for some of the pitfalls that could easily be dismissed every bit bad exercise, this is not always the case, every bit a critical assay uncovers structural and cultural issues inherent to collaborative work between academics and practitioners [57].

Reductionist, structuralist theories, such every bit rational choice-based theories of institutional change, provide straight forward recommendations for institutional design. They assume that actors will adjust to newly introduced or altered external institutions in a rational fashion, making institutional change predictable. However, the case for rational choice is rather weak in many cases. In local, urban water management, we debate that intended institutional alter is a multifaceted procedure that requires an open ontology and epistemology, perceptive of local weather condition and specificities. AR tin potentially contribute to finding such policies, which are meliorate fitted to serving the needs and capabilities of local communities by acknowledging and building upon the agency of such communities. This process of alter is what we will highlight in the following chapter.

five. The Case: Changing Urban Water Direction in Volos

5.one. The Research Setting

During the 2001/2002 Common Implementation Strategy (CIS) of the WFD, a series of Guidance Documents concerning all major aspects of its implementation were developed. A European network of 15 Pilot River Basins (PRB) was established in order to test the guidelines established in the documents. It was foreseen that PRBs would contribute to the implementation of the WFD, leading to the development of long-term implementation policies and guidelines and coherent River Basin Management Plans. Pinios River Basin in the region of Thessaly was the PRB of Hellenic republic that participated in the scheme. The overall aim of Pinios PRB was to identify the technical and management problems that may arise in the WFD implementation and to develop pragmatic solutions to these problems. Other aims were to test the practicability and efficiency of the technical and supporting Guidance Documents on key aspects of the WFD before they are applied at the national level in society to attain a concrete example of the application of these documents and to inform interested parties on the implementation of the WFD past involving the stakeholders (including local and regional authorities) in the process from an early stage. The PRB highlighted some indicative problems for the Greek context, simply, despite the difficulties encountered, several assessments characterized the project as a success, as well-nigh targets were successfully met and useful recommendations were made [47]. All the same, information technology failed to address—or better, did not engage—with issues of local importance, particularly those related to the inherited problem of water governance in Greece: a highly hierarchical and centralized administrative structure that leaves no space for the participation of local stakeholders [58].

The municipality of Volos, i of the largest urban agglomerations in Greece, is located in the prefecture of Magnesia, part of the Thessaly region, in fundamental Greece. One of the authors being involved in the European Project Intermediaries [59] conducted thorough enquiry on urban h2o management practices in the area. This was based on previous studies (mainly technical papers) and extensive interviews with the dominant actors in the local h2o sector. At this initial stage, the researchers identified the most of import pressures and bug of h2o resources. Such issues tin be summarized in the inadequate water quantity and quality during the summertime period, the pollution of the underground water reservoirs from uncontrolled disposal of industrial and agricultural wastes and conflicts between neighboring municipalities on h2o property rights [58]. Although an in depth review of these issues is beyond the scope of this paper and has been thoroughly discussed elsewhere [58,60], it must be noted that many issues were directly or indirectly related to the dysfunctional transactions and transformations taking place between the social and ecological system in the area and the institutions regulating them.

The intense interest of various stakeholders (NGOs, private sector, civil club) for further involvement in urban water management, combined with the implementation of a pilot river-basin (PRB) projection on the Water Framework Directive (WFD) in the region [61], raised expectations that the ground was fertile enough, in the sense of stakeholders' willingness to participate and accept responsibleness, to create possibilities for drastic improvements in the urban h2o management organization of Volos and changes in the institutional structures regarding water. As this picture was rather the effect of the intuition rather than the outcome of a long procedure of interaction between the interested parties, the major question that arose was: what form this alter would take and how information technology would be implemented? Would information technology follow the usual meridian-down, command and command, mostly administrative arroyo in Greek h2o governance reform or was this indeed an alternative with the potential to get a peachy show-instance? Also, if the potential was indeed in that location to design new institutions in a bottom-up way, would information technology be picked upwardly by the dominant state actors?

The researchers opted for an AR approach, hoping that information technology would initiate a process of deliberate alter, while information technology would permit the thorough observation and detailed study of the interactions taking identify between the stakeholders without influencing the outcome. During the initial stage, all the organizations and institutional actors involved in the area's water sector had been identified. Xiv key organizations (see Table ane) with unlike competencies, responsibilities and power were identified and classified in five categories: local government, state actors, private companies/entities, NGOs/civil society organizations and universities/research institutes. Following this phase, an initial mapping of the water problems and the h2o governance construction of the expanse was conducted, based mainly on previous studies and personal contacts. This valuable information constituted the background knowledge required to launch a procedure of joint dialogue with the actors who had been identified. It should be pointed out that during the process, more than stakeholders joined the initial group and contributed to the dialogue. Withal, for the purposes of this newspaper, we focus on those actors who took part in the network from the starting time to the very end.

Table ane. The xiv organizations that participated in the process of change (adopted by [59]).

| Category | Actor | Role | Institutional Power and Resource |

|---|---|---|---|

| State (National) | S1 | Public country institution, located in Volos, only functions regionally. Groundwater quality control, consultation to farmers. | Important, but but at the regional level |

| Local Government | G1 | Non-profit private company, run by the municipality. Water management, protection, supply, treatment, etc. | Absolute authority at the local level |

| G2 | Administration | Respected at the local level, only non focusing on h2o | |

| G3 | Municipal enterprise focused on urban development and regional planning in the prefecture. Conducts studies, construction and development of water works. | Not significant | |

| NGO/Civil Organization | N1 | Non-profit organization located in Volos and focused on crucial ecology problems, mainly related with the pollution of the adjacent gulf by wastewater. | Insignificant, some pressure |

| N2 | Network of denizen groups, voluntary organization, non-focused on environmental issues, but on the empowerment of Volos' civil society and the weakening of the state actors. | Insignificant | |

| N3 | Local, sub-regional environmental NGO. | Insignificant, some force per unit area, ties with N4 | |

| N4 | Network of Ecological Organizations. Headquarters located in Volos. In the past, much eco-activism and radical positions on environmental issues. Recently, ofttimes legal activeness taken confronting governmental actors. | Weak, merely often taken into account, as directly confrontation usually ends up in a courtroom room | |

| Academy/Enquiry | U1 | Public establishment, located in Volos, but agile in the greater area of Thessaly. Education and research. | "Knowledge holder", authority with "expertise" |

| U2 | Academy non-turn a profit research found. | "Knowledge holder", say-so with "expertise" | |

| Market | M1 | Individual commercial visitor, located in Volos, but provides services in the Thessaly Region. | Insignificant |

| M2 | Private company, based in Volos, but its products and services are exported globally. Research and innovation, especially on water handling installations. | Insignificant | |

| M3 | Commercial company located in Volos, but providing water sanitation products at the sub-regional level. | Insignificant | |

| M4 | Private company/clan based in Volos, but operating at sub-regional level. Industrial and household waste product water transfer and disposal. | Insignificant, simply with recognized technical knowledge |

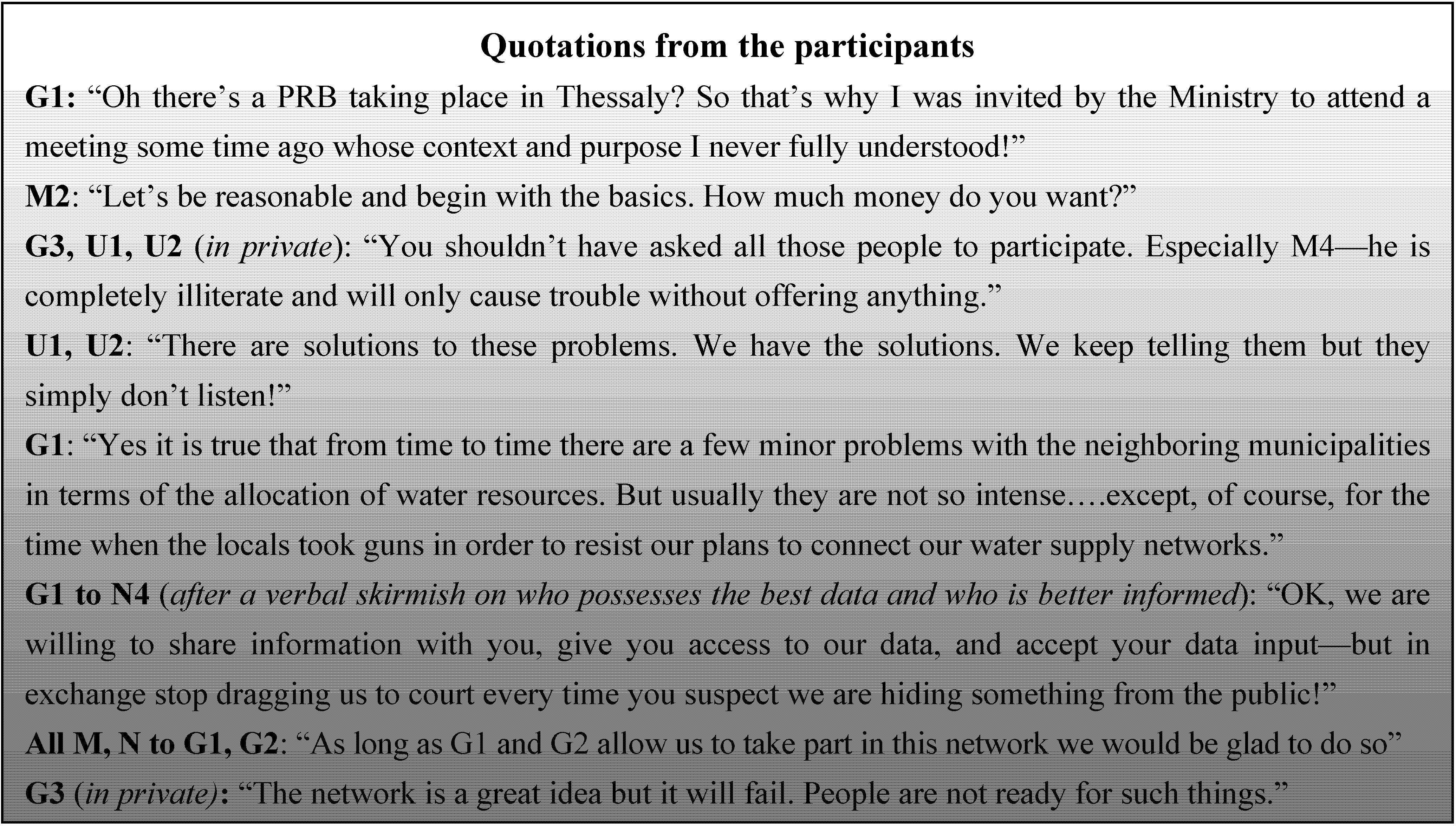

The meetings that followed the establishment of the network in 2004 opened up a wide dialogue on water and wastewater-related problems that exist in the expanse. Based on a background study drawing on a thorough literature review on documents related to the PRB and the processes related to the testing of the WFD in the area, the initial aim was to open up a discussion focusing entirely on these processes. This would allow the field researchers to identify how the emerging institutions would be adopted and what part the local actors would play in the pattern process. One of our principle assumptions was that all concerned would have heard of/been involved in the WFD (or at least the PRB that was taking place in their region), and then nosotros were shocked to find that not a single participant (including those formally engaged, co-ordinate to the literature) was aware of either! As a outcome, the researchers' idea of focusing on what was assumed as a problem of institutional alter and design was abandoned and reformulated co-ordinate to the participants' perceptions and capacities in line with AR'southward methodological steps. It gradually became apparent that there was a huge gap between theories of institutional change and practices described in the manuals of implementing participatory measures under the WFD, on one mitt [62,63,64], and the local reality (come across Figure 2), on the other.

Figure 2. Quotes describing the initial perception of the setting.

Figure 2. Quotes describing the initial perception of the setting.

Despite the groundwork study conducted and the theoretical propositions on water governance and institutions and the value of participation the researchers brought into play, the actual situation in the surface area was however largely unknown to the researchers and was non necessarily reflecting the fashion in which change in fact took place. These initial observations highlighted the need for ontological and epistemological openness in gild to facilitate the multifaceted institutional modify necessary for successful implementation of the WFD. Based on this preliminary conclusion, the researchers causeless a facilitating role in the ongoing process of change, where the field researchers could observe that subtle change was already taking place, without trying to influence it towards a certain direction. AR offered a methodological framework of continuous cyclical steps of planning, activeness, observation and reflection (come across Figure 1) that, on one hand, would allow researchers to structure their work scientifically, while assuasive the locals to pb the procedure of finding ways to bargain with what they themselves considered water problems.

5.two. The Use of AR to Facilitate Intended Multifaceted Institutional Change

A network of stakeholders was established as an experimental, pioneering forum to discuss and address disquisitional water management problems in a more participatory and innovative manner that would first foster social learning [65] and would further enable deliberation of the stakeholders, resulting in the emergence of new collective rules to deal with existing problems. Within this process, the field researcher'due south agile part could exist characterized as "initiator", "facilitator", "bridge builder" and, from a certain bespeak onwards, simply "observer".

Our facilitating research was based on structured and unstructured questionnaires, interviews and the devoted post-obit upwardly of the network's meetings. In order to identify people's motives for joining the network, their perception of local problems and their expectations of the network, we used a questionnaire, which was circulated at the early stages of the research. A second series of interviews took place one-and-a-half years after the institution of the network, in order to assess the learning experience of members inside the network, identify occurred and ongoing changes in perceptions, but likewise grasp changes in the water direction practices. Additionally, we maintained open channels of communication with each member of the network at all times and organized numerous informal meetings (restaurants, cafes, bars, etc.) based on an open up invitation, at which some of the most interesting developments and discussions took identify. This approach strengthened the relationships between the participants considerably. The steps were carefully designed, so every bit to include individual- and group-level contributions in the planning. As the first "bicycle" (see Figure 1) of our action enquiry came to a close, problems identified at the outset had been largely reformulated by the participants.

Until late 2005, we carefully assessed the ideas that were presented during the meetings. Nosotros observed, planned, acted, inverse and re-researched certain issues that arose. We critically reflected on our activities in a systematic and cyclical style, gradually gaining deeper insights into what locals considered important, what institutions in place were dysfunctional and what might be a structure that could replace them [66]. For example, shared responsibleness concerning urban water management activities was ensured via the establishment of a conflict resolution mechanism that included a abiding flow of information, release of information whenever required past a network member, announcement of planned decisions before their implementation and efforts to accomplish consensus. Fifty-fifty a potential legal dispute between an NGO and the water utility was swiftly dealt with jointly and solved before reaching the courtrooms. Following this logic, five organized meetings and workshops took identify (one–2 days each), in addition to an "extra" meeting that was requested by many participants equally a response to an urgent situation (wastewater leakage). There had likewise been ii meetings with primary pedagogy representatives (with the aim of taking mutual action on environmental instruction activities), 1 press release, i conference and numerous completely informal private or group meetings.

Through further facilitation and collaborative activities (eastward.yard., a joint conference, publication of leaflets, public awareness activities, etc.), diverse attempts were fabricated to get-go plant and then reinforce a communicative space for deliberation betwixt equal participants. However, limits to establishing this Habermasian platonic kept arising, such as difficulties of changing the traditional relationship between local people and local government, the lack of a sense of self-efficacy, the inadequate rhetoric skills of some participants and the lack of self-confidence of powerless actors to express their opinion.

v.3. Offset Results of AR in Facilitating Intended Multifaceted Institutional Change

The "outside the network" informal meetings (sometimes more than lengthy, time-consuming and passionate than the regular meetings) proved extremely helpful, cementing strong personal ties between the participants and providing a deep insight into each other'due south views and ways of reasoning.

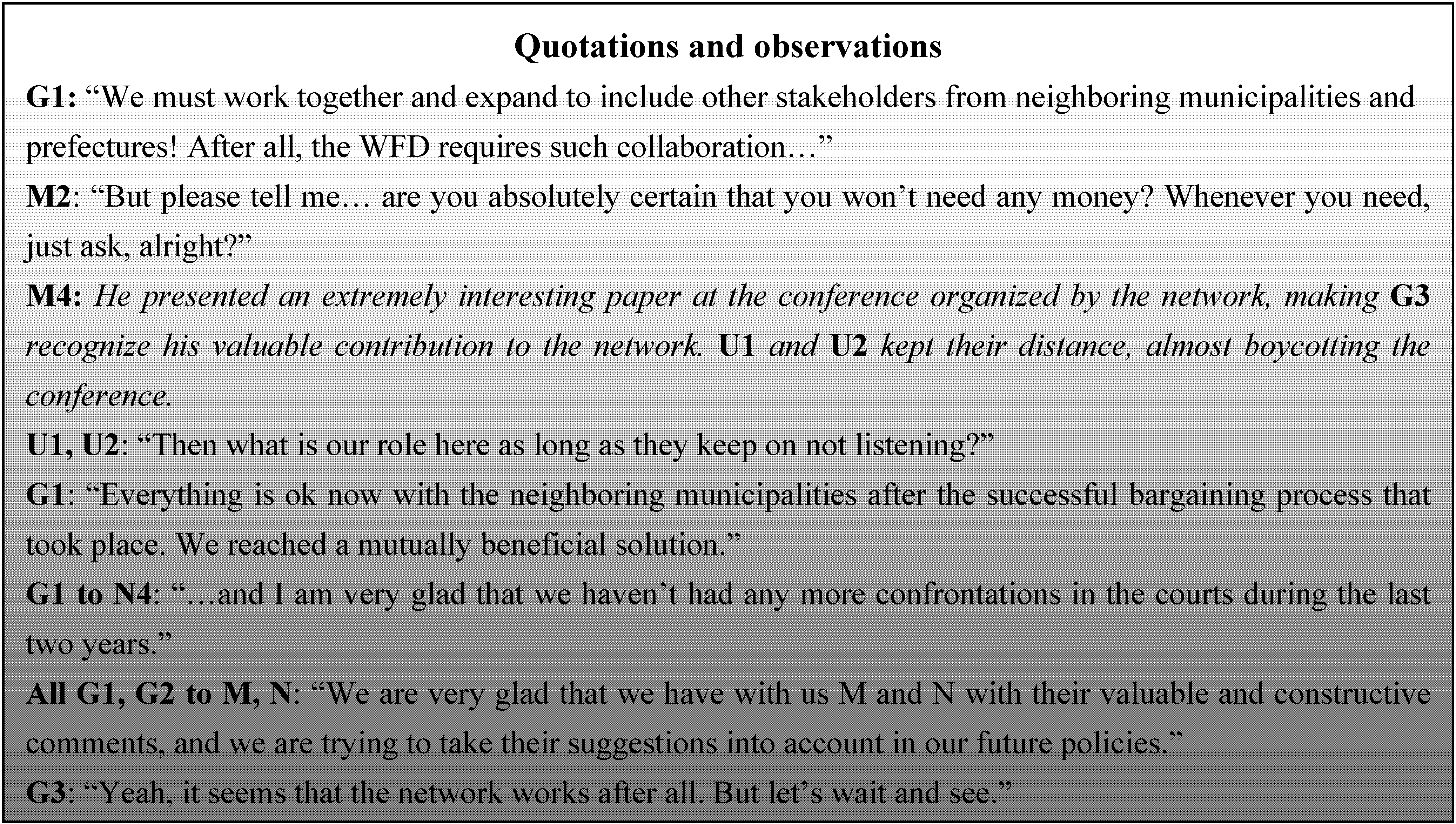

Whatsoever conflicts that emerged between the participants were solved by ways of dialogue and negotiation. Every bit time went on, the almost active members of the network developed greater expectations and envisaged broadening the scope and the range of the network to cover issues exterior the metropolitan region of Volos (such as water for agriculture). In parallel, they sought support from other European examples of water direction bug in an attempt to improve their knowledge. What was an amazing experience for united states of america equally scientists and researchers, though, was to observe the way the participants' behavior changed over fourth dimension (meet Figure iii).

Figure three. The amazing experience of a changing reality.

Figure three. The amazing experience of a changing reality.

From only the second meeting onwards, the shared leadership amid the network's members and the horizontal construction of the network itself facilitated a more fruitful and open dialogue. Some participants realized the opportunities to improve their knowledge and put considerable time and attempt into the network (e.g., M2), while others maintained a distance or even displayed elitist behavior (U1, U2). Despite this, the stakeholders' grouping had already developed its own dynamic, which resulted in a gradual willingness to acknowledge the contributions of certain (initially less highly regarded) participants, on the one hand, and a tendency to disregard unproductive interventions on the other, regardless of the institutional ability and influence of those making them. At this betoken, the WFD and the PRB had been completely taken out from the agenda, and the stakeholders were focusing entirely on finding responses to their local problems related—but non express—to urban h2o management. Despite the growing interest of the researchers on the evolving process of alter, their formal interest was concluded, and they departed from the area.

5.four. Post-Evaluation of Action Inquiry

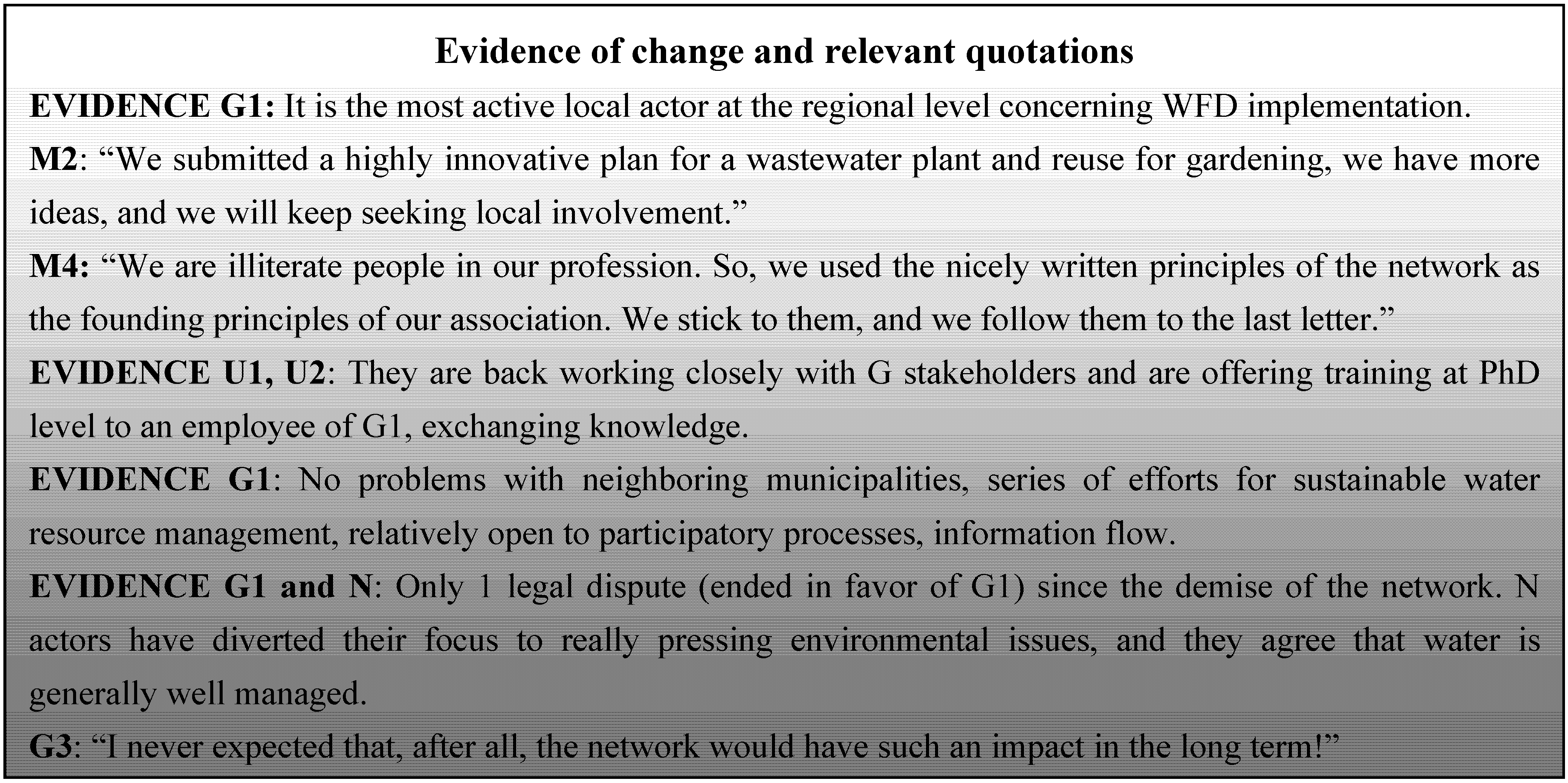

More than than seven years have passed since this exercise. Withal, in a post-evaluation attempt, we contacted the participants, and we tried to identify the actual changes that occurred. The implementation of the WFD was again a primal issue for our inquiry. The summary of our findings is presented in Figure 4.

Figure iv. Summary of post-evaluation findings (in 2009).

Figure iv. Summary of post-evaluation findings (in 2009).

More specifically, we noticed that G1 is constantly looking for opportunities to interact with other local and regional stakeholders from diverse sectors and to institutionalize this cooperation. G1 is now involved actively in issues directly linked to the implementation of the WFD and has had a considerable influence on changing the—initially completely unrealistic—plans to restore the stale upwardly Lake Karla inside the Pinios River Basin as a drinking h2o reservoir and instead use the water for irrigation. In institutional terms, G1 is withal responsible but for domestic and industrial water supply inside the urban area. However, through its date in the new restoration plan with which groundwater quantity and quality will exist enhanced, G1 acquired valuable knowledge and experience on broader h2o direction issues through its shut collaboration with other local stakeholders.

Moreover, the local academics and researchers are now working closely with local stakeholders on various projects and have abased their "elitism". An employee of G1 is existence trained at the PhD level at the local university, and every bit has been pointed out, the exchange of knowledge is a two-mode process. G1 acquires scientific knowledge and expertise, while the university receives the practical and technical information it was lacking. In addition, university students pay regular visits to the water utility's installations and conduct research at the Ph.D. level on urban water management, laying the foundation for even closer cooperation in the future.

Conflicts from the past have been resolved nearly entirely, and culling dispute resolution mechanisms have been adult and internalized by the stakeholders of Volos. Negotiation, bargaining and communication now institute the key to resolve disputes, either within the Metropolitan Area or between Volos' stakeholders and neighboring communities or regional and national actors. Information technology is very of import that this overall shift in the way of how problems between stakeholders are at present conceptualized and resolved, and it has resulted in a strategic rethinking of the N stakeholders, who now concentrate on urgent environmental or social issues in the area and non on water bug, on which they work closely with G actors. Since 2004, there has been only ane problem that was resolved in the court room. Afterward, the N histrion that pushed the issue to the very stop and admitted in an interview that it was more than a spasmodic action of confrontation reflecting the old civilization that prevailed in the past than a really necessary activity today.

M2 has proven its character as a pioneer of eco-preneurship [67] companies in Hellenic republic, combining genuine environmental concerns with profit-oriented business. An ambitious program for wastewater handling was submitted to the municipal authority, while the visitor's water handling services are at present used by the tourism industry of the area. Moreover, there is collaboration with the local university on water innovation issues. According to the M2 participant, the insights offered by the network greatly facilitated these activities.

Perhaps the near personally rewarding feedback comes from participant, M4, who was the object of much discontent during the network's operations. At present, having reinforced its position as being president of a local association of wastewater transfer tankers, he stated that the learning he caused through the network really informed the principles of the clan. Now, water protection is the principle guiding the companies' operation, and incidents of illegal disposal have ceased to be. Moreover, the association operates in harmony with the other stakeholders, contributing to the wastewater direction efforts of the utility.

Finally, although it is difficult to measure out, it seems that the wider order is responding to and interacting better with water-related bug. According to the participants interviewed, the citizens' sensation has increased, as has the accountability of the utility and public credence and legitimacy of water-related works.

It seems that the employed AR did, later all, have a considerable affect, not simply on the participants, just also on the local customs as a whole in terms of deliberate institutional change. The bottom-up participatory process that took place, a concept completely alien to the region's social norms, influenced the perceptions of the members of the network to the point of altering their behavior. AR enhanced communication, offered a mutual vision and sparked a process of cognition substitution, collective learning and joint activeness, which, although not constituting the solution to urban water management problems, can be viewed as a precondition for resolving these problems. Moreover, it created a shared pool of resources that may later contribute towards the implementation of the WFD.

More specifically, the dominant local actors realized that through participation, fifty-fifty institutionally weak stakeholders can influence a process; as a upshot, they played a major part at the regional level, despite the fact that their institutional ability was practically not-real. Moreover, the participants recognized that there is not 1, only many subjective realities in relation to water issues and that, through word, these realities can emerge to formulate a "reality-rich framework" in which all stakeholders tin work together constructively. Seen in this perspective, conflicts can be solved through negotiation and word, and judicial mechanisms are only measures of last resort. A process of institutional change had been initiated through the network of participants. Dialogue slowly became the norm, and this immune the convergence of different, often alien, interests of stakeholders. It allowed the identification of common problems and offered ways to solve them. Legitimacy and public credence of the taken decisions supported the change of onetime ineffective urban water direction practices. Finally, it resulted in new water institutions, albeit many of them informal in the sense of constraints self-imposed by the actors, unofficial rules of acquit and norms adult between members of the participants' network, that, under legitimization and public acceptance acquired through the AR, tin be observed today in various ways (for case, joint h2o projects, institutionalization of information and resource sharing, public awareness campaigns). Tragicomic practices of the by, like informing the public with a megaphone and relying on rumors to control h2o demand (see Figure 5), were never to be repeated.

Figure 5. Practices of the past.

Figure five. Practices of the past.

6. Conclusions

Based on our empirical research findings and subsequent analysis, we claim that AR meets the challenge of scoping the field of urban water management in an open fashion for determining the advisable procedure of institutional modify.

Although a serial of articulation actions indicating growing collective responses to common h2o direction problems had taken identify during the functioning of the network, the authors have opted to exit a detailed listing aside and focus on the changes that followed (from 2006 to 2010). It must exist noted, though, that the results of the detail case in relation to the PRB plan and bug of public participation and the production/exchange of knowledge within an informal social network have recently been published [58,60]. In this paper, instead, the authors focus on the role that the AR played in the creation of new rules of conduct, the new formal and breezy structures shaping the behavior of the stakeholders in Volos and the changes that followed. Thus, they fence for the methodological value of AR in a setting of changing urban water institutions.

Nosotros discussed changes in institutions that need to be enacted by actors every bit subjects of institutions and which, consequently, need to change their behavior. Very unlike conceptions exist with regards to how this process unfolds and why actors modify institutions. As our case has shown, a gap between an imposed new institutional framework (WFD) as manifested through the implementation of a PRB and the change the actors-subjects to institutions require may be considerable. The role of the researcher here, through an action research methodology, may facilitate the process of institutional change and the emergence of new institutions towards the direction required. This does not necessarily mean that the result of such a process will conclude to the "desired" change, in this example, the successful implementation of WFD, just it might constitute a commencement crucial step. In such a case, we argued that the by-products of the process, equally shaped by the actors (changes in urban water management practices, emergence of new institutions, fostering participation, increasing awareness and empowering local stakeholders), indirectly, only all the same, significantly, contribute to the overall targets of the WFD.

In our instance, the purposive design for the desired change, required for the introduction of new water institutions, according to the WFD's requirements, as experienced through the PRB, was found to exist extremely weak. The objective institutional design that the researchers attempted failed from the very beginning. Once a subjective-dialogic institutional blueprint procedure was initiated, though a process of deliberate identification and evaluation of new systems by the actors, did this result in the emergence of new institutions inclusive to what the actors perceived as socially preferred outcomes.

By employing AR, we explored how structures shape agents' beliefs and what data we need to assemble in order to produce cognition about this behavior. During the procedure, the actors themselves, through a deliberation process, offered the answer to the above questions, allowing the researchers to report the structures and facilitate the process of change towards the subjective, but still socially desired, direction.

In our case, nevertheless, simply as the different theoretical suggestions on institutional change propose, different actors followed unlike logics, converging at the aforementioned result: the emergence of new institutions crafted for the local conditions and problems. This suggests a rather dialectical view of institutional change that provides a more coherent footing upon which we tin track the value of activeness research equally a methodology.

In this context, AR actually worked every bit the lubricant between the different rationales and rationalities of the actors towards institutional alter as decided past themselves (subjective-dialogic institutional pattern).

Attempting to reflect on theoretical propositions on how institutions dynamically change, our findings strongly support the argument that:

"[i]n practice, processes such as learning, socialization, diffusion, regeneration, deliberate design and competitive selection, all have their imperfections and an improved agreement of these imperfections may provide a central to a better agreement of the dynamics of rules" ([68], quoted in [69], p. 17). Activeness research in this context, provided a platform on which the understanding for each ane of the above-mentioned processes became possible, not only for the involved stakeholders, but for the researchers every bit well, in a way that they were able to facilitate the process of modify without influencing it towards a certain direction.

In this conception, institutional alter following institutional design tin sally every bit an result of changes of perceptions about roles, identities, normative values, cognitive frames and rules. The outcomes of institutional blueprint are essentially unpredictable in this context, just depend on the specificities of the trouble state of affairs and the way in which experience, skilful knowledge or intuition are applied. Enhancing communication, fostering social learning, structuring of processes for information commutation, edifice of trust and developing dispute resolution mechanisms proved indispensable components for success, although they were initially viewed as issues of secondary importance to the research object. Indeed, our example shows that the results of the procedure had been rather unpredictable, and they evolved around specificities of problems that nosotros as researchers were unable to conceive of prior to—but besides during—the process. This became but possible when the first author returned to the "crime-scene" two years subsequently AR was over. This provided a deep insight into the actual changes that had taken place and hinted at prospects for further modify. The amount of time that elapsed between the starting time evaluation (based on the participants' views in one case the network had demised) and the second evaluation, which took place in 2009, covered a wide noesis gap on the touch on of the action research conducted in the past and, additionally, highlighted certain aspects of institutional change that we were not able to predict. This time gap between the conclusion of a procedure and the first tangible results related to institutional change might plant a fundamental element for evaluating the actual success of measures required past the WFD. Moreover, AR may provide a structured, just still open, methodological tool to support processes, culling to the largely mechanistic procedures of "ticking boxes" adopted to a large extent, especially apropos the PRBs.

Summarizing our conclusions, we distinguish the value of our findings in a broader setting of urban water management, and nosotros draw some lessons based on our instance analysis through the lens of institutional change. In short, we claim that Action Research provides a paradigm for the way a researcher can exist involved in the implementation processes of policies aiming at changing the h2o institutions, but oftentimes implying a requirement to change a whole series of other institutions and even beliefs, perceptions and culture. Our example highlighted the importance of the timing of such an involvement, equally the initial findings of a long process that aims at changing long-standing and deeply rooted institutions may significantly differ when seen from a longer time perspective. In settings where the purposive design of the desired change might neglect, action researchers might back up a shift towards a subjective-dialogic institutional design and function as the lubricant between different interests, rationales and behaviors and spark the process of change. Nonetheless, the researchers employing such an approach must be aware that the results might be socially desirable, but not necessarily uniform with what upper-level political decisions or state/European policies dictate.

Acknowledgements

The newspaper was inspired past the Sustainable Hyderabad—Albrecht Daniel Thaer Kolloquium that took place in Berlin in June 2012 on "Crafting or Designing: Intended Institutional Change for Social-Ecological Systems", supported by the German Ministry of Education and Research and the Heinrich Böll Foundation. The field research was financially supported by the European Matrimony (European Committee, New Intermediary Services and the Transformation of Urban Water Supply and Wastewater Disposal Systems in Europe, EVK1-CT-2002-00115 [59]; Marie Curie RTN GoverNat, Contract No. 0035536 [70]). The authors are grateful to Zefi Dimadama and Panagiotis Getimis for their vital involvement in the empirical inquiry. Nosotros are indebted to all stakeholders and citizens and the local regime of the Municipality of Volos for their honesty and constant back up during and subsequently the activity research.

References

- Limburg, Yard.E.; O'Neill, R.Five.; Costanza, R.; Farber, Due south. Complex systems and valuation. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderies, J.M.; Janssen, M.A.; Ostrom, Due east. A framework to analyze the robustness of social-ecological systems from an institutional perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2004, nine. Available online: http://world wide web.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss1/art18/ (accessed on 25 March 2013). Article eighteen. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.s. 2007, 104, 15181–15187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.Due south.; Gunderson, Fifty.H. Resilience and Adaptive Cycles. In Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human being and Natural Systems; Gunderson, 50.H., Holling, C.S., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, Us, 2002; pp. 25–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gatzweiler, F.; Hagedorn, K. The evolution of institutions in transition. Int. J. Agric. Resour. Gov. Ecol. 2002, 2, 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Goodin, R.East. The Theory of Institutional Pattern; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bobrow, D.B.; Dryzek, J.South. Policy Analysis by Design; University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2000/sixty/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 Oct 2000: Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of H2o Policy; Official Periodical of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2000; Volume 43.

- Council Directive 76/160/EEC of 8 December 1975: Concerning the Quality of Bathing H2o; Official Journal of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 1976.

- Council Directive 76/464/EEC of 4 May 1976 on Pollution Caused by Certain Dangerous Substances Discharged into the Aquatic Surround of the Community; Official Journal of the European Communities: Grand duchy of luxembourg, 1976.

- Quango Directive 80/68/EEC of 17 Dec 1979 on the Protection of Groundwater against Pollution Caused by Certain Dangerous Substances; Official Journal of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 1980.

- Council Directive 91/676/EEC of 12 December 1991 Apropos the Protection of Waters against Pollution Caused by Nitrates from Agricultural Sources; Official Journal of the European Communities: Grand duchy of luxembourg, 1991.

- Council Directive 91/271/EEC of 21 May 1991 Apropos Urban Waste-H2o Treatment; Official Journal of the European Communities: Grand duchy of luxembourg, 1991.

- Kaika, K. The Water Framework Directive: A new directive for a changing social, political and economical European framework. Eur. Program. Stud. 2003, 11, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoccaro, G.; Prosperi, Yard.; Zanni, G. Economic furnishings of legislative framework changes in groundwater utilise rights for irrigation. Water 2011, 3, 906–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetropoulou, L.; Nikolaidis, N.; Papadoulakis, V.; Tsakiris, Thousand.; Koussouris, T.; Kalogerakis, N.; Koukaras, G.; Chatzinikolaou, A.; Theodoropoulos, K. Water framework directive implementation in Greece: Introducing participation in water governance—The case of the Evrotas river bowl direction plan. Environ. Policy Gov. 2010, twenty, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, T.; Klauer, B.; Manstetten, R. The surroundings as a challenge for governmental responsibility—The example of the European Water Framework Directive. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2058–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folio, B.; Kaika, One thousand. The EU Water Framework Directive: Part 2—Policy innovation and the shifting choreography of governance. Eur. Environ. 2003, 13, 299–316. [Google Scholar]

- Bressers, H.; Kuks, S. Integrated Governance and H2o Basin Management: Conditions for Regime Change and Sustainability; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, Holland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Borowski, I.; Le Bourhis, J.-P.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Barraque, B. Spatial misfit in participatory river basin management: Furnishings on social learning, a comparative assay of german and french case studies. Ecol. Soc. 2008, thirteen. Available online: http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00416005/ (accessed on 26 March 2013). Article 7. [Google Scholar]

- Borja, A. The European h2o framework directive: A challenge for nearshore, coastal and continental shelf research. Cont. Shelf Res. 2005, 25, 1768–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohaupt, V.; Crosnier, G.; Todd, R.; Petersen, P.; Dworak, T. WFD and agriculture activity of the European union: First linkages betwixt the CAP and the WFD at EU Level. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 56, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Liefferink, D.; Wiering, M.; Uitenboogaart, Y. The Eu Water Framework Directive: A multi-dimensional analysis of implementation and domestic touch. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieperink, C.; Raadgever, G.T.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Smit, A.A.H.; van Rijswick, H.F.M.W. Ecological ambitions and complications in the regional implementation of the Water Framework Directive in the Netherlands. Water Policy 2012, xiv, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravesteijn, W.; Kroesen, O. Tensions in h2o management: Dutch tradition and European policy. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 56, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, N.; Howe, J. Implementing the European union water framework directive: Experiences of participatory planning in the ribble basin, north west England. Water Int. 2006, 31, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, R.; Roeling, Due north.; Watson, D. Challenges to science and guild in the sustainable management and use of water: Investigating the office of social learning. Environ. Sci. Policy 2007, 10, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.A.L.; Fritsch, O. Operationalising active involvement in the EU Water Framework Directive: Why, when and how? Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 2268–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, A.A. Conflict and Cooperation: Institutional and Behavioural Economic science; Blackwell: Malden, MA, U.s.a., 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Paavola, J.; Adger, W.Due north. Institutional Ecological Economics. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 53, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, D.Westward. Economic Interests and Institutions: The Conceptual Foundations of Public Policy; Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn, K. Item requirements for institutional analysis in nature-related sectors. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2008, 35, 357–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brousseau, E.R.E. Climbing the hierarchical ladders of rules: A life-cycle theory of institutional evolution. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 2011, 79, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatn, A. Institutions and the Environs; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, Uk, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.Y. An economic theory of institutional change: Induced and imposed change. Cato J. 1989, 9, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P.A.; Taylor, R.C.R. Political science and the iii new institutionalisms. Polit. Stud. 1996, 44, 936–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theesfeld, I. A Mutual Pool Resource in Transition: Determinants of Institutional Change for Bulgaria's Postsocialist Irrigation Sector; Shaker: Aachen, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J. Institutions and Social Disharmonize; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, Britain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- March, J.Yard.; Olsen, J.P. Autonomous Governance; Free Press: New York, NY, United states of america, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, 1000. Institutions as cognitive media between strategic interactions and individual beliefs. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 2011, 79, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, G.M. Institutions and individuals: Interaction and evolution. Org. Stud. 2007, 28, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, Thousand.M. The approach of institutional economics. J. Econ. Lit. 1998, 36, 166–192. [Google Scholar]

- Stagl, S. Theoretical foundations of learning processes for sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Globe Ecol. 2007, 14, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Due north, D. Institutions, Institutional Alter and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Printing: Cambridge, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutional Change: A Framework of Analysis, 1994. 1994. Available online: http://ideas.repec.org/p/wpa/wuwpeh/9412001.html#provider (accessed on 10 October 2007).

- Alexander, Due east.R. Institutional tranformation and planning: From institutionalization theory to institutional design. Programme. Theory 2005, 4, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. The Solution of A Chronic Conflict in Manufacture. In Proceedings of the Second Brief Psychotherapy Council; Plant For Psychoanalysis: Chicago, IL, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Colliers, J. United states Indian Administration as a laboratory of indigenous relations. Soc. Res. 1945, 12, 265–303. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Theory in Exercise: Increasing Professional person Effectiveness, 1st ed; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, D.J.; Levin, M. Introduction to Action Research: Social Research for Social Change; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, P.; Bradbury, H. Handbook of Action Inquiry. Participative Enquiry & Practice; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Torbert, W. The Do of Activity Inquiry. In Handbook of Activeness Research. Participative Inquiry & Exercise; Reason, P., Bradbury, H., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2001; pp. 250–260. [Google Scholar]

- Coghlan, D.; Brannick, T. Doing Action Research in Your Own Organization, 2nd ed; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed; Sage Publications: 1000 Oaks, CA, United states of america, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, P.; Bradbury, H. Handbook of Action Research, 2nd ed; Sage: London, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, 5.J.; Rogers, T. There is nothing so theoretical every bit skillful action research. Activity Res. 2009, 7, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchy, Thou.; Ahmed, S. Social Learning, academics and NGOs: Can the collaborative formula piece of work? Action Res. 2007, 5, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikos, D. Community Involvement in the Implementation of the WFD in Greece. In Ambientalia Special Issue Series (II): Ten Years of the Water Framework Directive—An Overview from Multiple Disciplines; Martín-Ortega, J., Matarán, A., Eds.; Edificio Politécnico: Granada, Spain, 2010; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- New Intermediary Services and the Transformation of Urban Water Supply and Wastewater Disposal Systems in Europe. Bachelor online: http://cordis.europa.eu/search/index.cfm?fuseaction=proj.document&PJ_RCN=5907329 (accessed on 10 October 2012).

- Dimadama, Z.; Zikos, D. Social Networks as Trojan Horses to Claiming the Authority of Existing Hierarchies: Knowledge and Learning in the Water Governance of Volos, Hellenic republic. Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 24, 3853–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Progr. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Public Participation in Relation to the Water Framework Directive; Guidance Certificate No. 8; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2003.

- European Commission, Guidance on Public Participation in Relation to the Water Framework Directive: Active Involvement, Consultation, and Public Access to Information; Guidance Document on Public Participation; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

- Wilcox, D. The Guide to Effective Participation; Delta Press: Brighton, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mostert, Due east. Public Participation and the European Water Framework Directive: A Framework for Analysis; 2003; Bachelor online: http://www.harmonicop.uni-osnabrueck.de/_files/_down/ HarmoniCOPinception.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2010).

- Wadsworth, Y. What is participatory activeness research? 1998; Paper 2. Available online: http://www.scu.edu.au/schools/gcm/ar/ari/p-ywadsworth98.html (accessed on 26 March 2013).

- Beveridge, R.; Markantonis, V.; Zikos, D. Eco-Preneurship in the Water and Wastewater Sectors of the Northward East Of England and the Volos Region (Greece). In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Environmental Science and Engineering (CEST), Rhodes, Hellenic republic, i–3 September; 2005. Available online: http://www.srcosmos.gr/srcosmos/showpub.aspx?aa=6444 (accessed on 8 March 2011). [Google Scholar]

- March, J.G. Divisional rationality, ambiguity and the engineering of choice. In Rational Choice; Elster, J., Ed.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- March, J.M.; Olson, J.P. The Logic of Appropriateness; Arena Working Papers WP 04/09; Loonshit Center for European Studies: Oslo, Norway, 2004; Bachelor online: http://www.sv.uio.no/loonshit/english/research/publications/loonshit-publications/workingpapers/working-papers2004/wp04_9.pdf (accessed on 28 Jan 2013).

- GoverNat Home Folio. Available online: http://www.governat.eu/ (accessed on 8 March 2013).

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and weather condition of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/three.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/5/2/356/htm

0 Response to "All Art Is a Tragicomic Holding Action Against Entropy"

Post a Comment